Feik asks:

How do I know which Finnish i-word is “new” and which “old”? kieli: kielen vs tiimi: tiimin?

My answer:

From your question, I can tell that you know a lot of Finnish already, hyvä sinä! I’m going to start from the beginning for the readers who don’t, so please bear with me.

Finnish has fifteen cases, which are little bits of sound that we stick at the end of words to express things like where something is situated. English, for example, expresses these same ideas with prepositions (which, by the way, there are also a lot of and it can be really hard to know which one to use).

So in English, you’d say for instance that someone is

in the garden.

In Finnish, that would be

puutarha + ssa

garden + in

Not too hard, right? As a bonus, no pesky article to decide on. For a lot of Finns, it’s mind bogglingly hard to know if they should say that they’re in a garden or in the garden this time. I don’t know where English gets it’s reputation for being easy to learn.

However, here comes the hard part: a lot of Finnish words change when you stick a case marker on them. For instance, all words ending in nen do this:

suomalainen puutarha

Finnish garden

suomalaise + ssa puutarha + ssa

Finnish + in puutarha + in

suomalaisessa puutarhassa

in a/the Finnish garden

Whenever a word ends in nen , the nen becomes se:

suomalainen ‘Finnish’ -> suomalaisessa ‘in the Finnish’

iloinen ‘happy’ -> iloisessa ‘in the happy’

Nikonen ‘the teacher’s last name’ Nikosessa ‘in the Nikonen’

The really hard part is, you can’t always tell which word group a word belongs to just by looking at it, and this is where we get to you the question of the day, new and old words ending in i.

When a word ends in i, there are four word groups it might belong to:

1. HOTELLI-words

These are the new words that Feik is referring to. In this word group, the endings are just stuck on and nothing strange happens. These words are relatively new loan words, and if you speak English or Spanish for example, you’ll recognize a lot of them straight away.

bussi -> bussissa

tomaatti -> tomaatissa

normaali -> normaalissa

Maybe you can guess what those words mean.

2. SUURI-words

In these words, the i at the end transforms into an e before the endings.

suuri ‘big’, i -> e

-> suure + ssa ‘big + in’

= suuressa ‘in the big’

kieli ‘language’ i -> e

-> kiele + ssä ‘language + in’

= kielessä ‘in the language’

You might have noticed ssä for in. Yeah, we have two versions of in, ssa and ssä.

Also, SUURI-words are irregular in the partitive case (which literally means a part of something):

suuri ‘big’ suurta ‘a part of a big’

kieli ‘language’ kieltä ‘a part of a language’

3. LEHTI-words

As with SUURI-words, the i becomes an e before the ending. Also, there may be a kpt-change, but that deserves it’s own post or three.

lehti ‘newspaper’ t -> d, i -> e lehde + ssä ‘newspaper + in’ lehdessä ‘ in the newspaper’

LEHTI-words are only different from SUURI-words because the partitive is regular.

lehti ‘ newspaper’ lehti + ä ‘newspaper + a part of a’ lehteä ‘a part of a newspaper

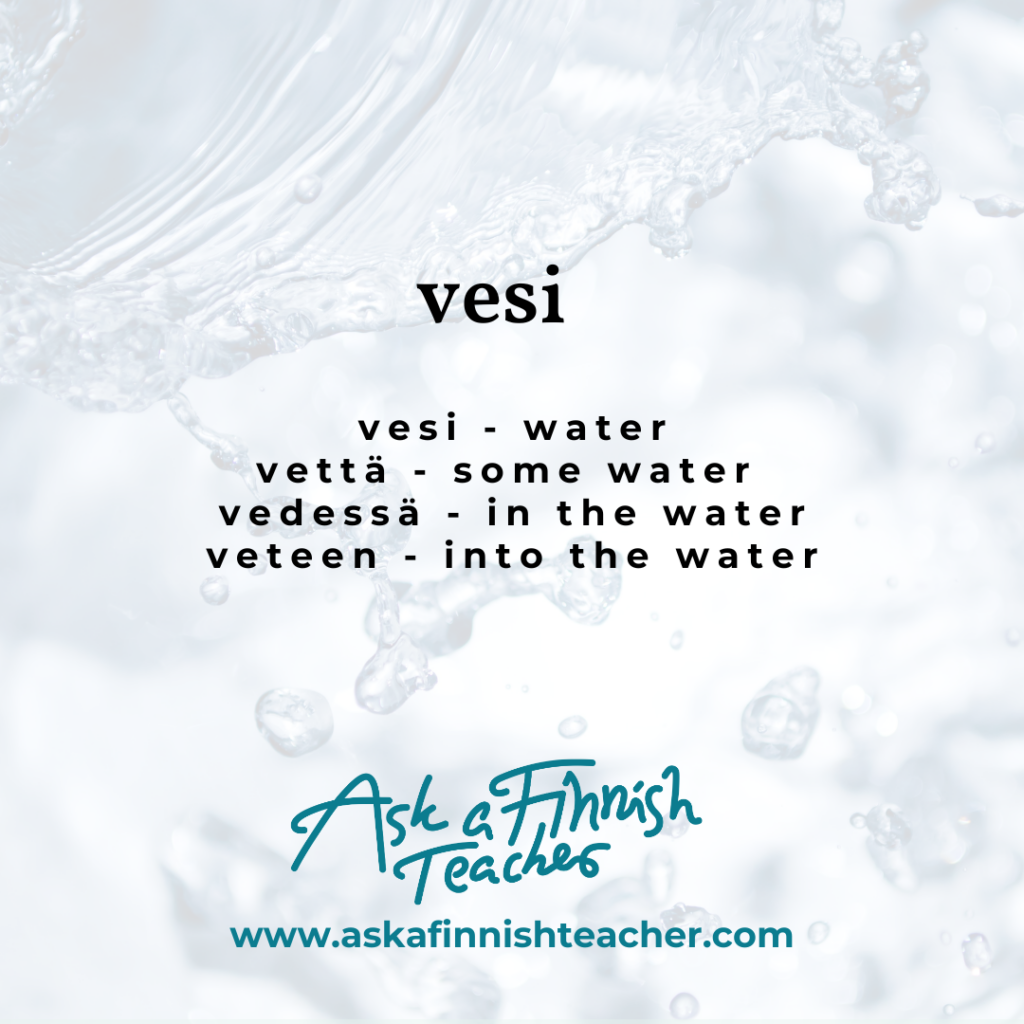

4. VESI-words

This word group is a group of very old words, from the time where all we had out here was water, our hands, some wolves and years and years of time.

vesi ‘water’

vede+ssä ‘water + in’ = vedessä ‘in the water

vettä ‘ some water’ (the partitive, so more literally, ‘a part of water’)

When you come across a new Finnish word ending in i, look it up and see which group it belongs to. A good tool for this is the free online Finnish dictionary Kielitoimiston sanakirja , which is a great quality dictionary carefully refined by language professionals for decades and updated regularly.

There are some clues, of course. If it sounds familiar from English, French, Latin, German, Russian, Swedish etc, it’s probably a HOTELLI-word. If it’s something that’s always been around in Finland, it’s probably one of the other three. If it ends in si, it’s probably a VESI-word.* But there’s really no other option than just memorizing, I’m afraid.

*I edited this part a bit after some comments from a kind colleague, it originally read:

If it ends in si and is something that has always been around in Finland, like susi ‘wolf’ or käsi ‘hand’, it’s probably a VESI-word.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.